As a swirl of virtual sound is abruptly silenced, the darkness of the theatre is illuminated by the solitary light of a laptop screen. A young man sits alone in his bedroom and tries to rewrite who he is. His first draft fails. The second unleashes a chain of events that goes far beyond anything he could have conceived of, a version of himself both momentous and monstrous, kind and cruel, hated and loved.

Or, depending on your reading, a nascent sociopath sits in the dark and begins his plan to abuse and manipulate an innocent family.

Dear Evan Hansen has proved a divisive piece of musical theatre, building an ardent and vocal fanbase followed by a somewhat inevitable backlash as people questioned its success, its quality and ultimately its morality.

For those unfamiliar with the story, Evan Hansen is a seventeen year old high school student trying to manage life with social anxiety and nursing a broken arm after a fall from a tree.1

An assignment from a therapist tasks him with writing positive letters to himself about himself. One of these letters ends up in the hands of Connor Murphy, an equally troubled classmate whose sister Evan is romantically fixated on. When Connor commits suicide with this letter in his posession his grieving parents look to Evan to ease their pain, believing their son wrote his suicide note to Evan, that he did have a close friend and that he wasn’t alone in life and death. Evan feels obliged to construct an entirely fictional friendship with Connor for the Murphys, a vision of an alternate existence that spirals out of control as he begins to feel gratified and validated by his new persona and the social benefits it offers him.

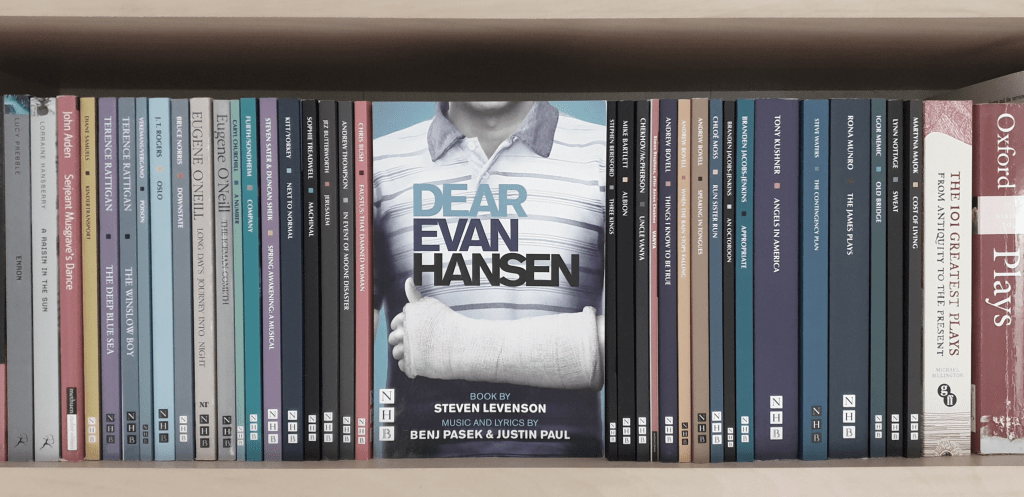

Unusually, rather than experiencing this “play with music” in the theatre, my first encounter with it was through reading. Part of Nick Hern Books’ Playscript Subscriptions, a copy of the text arrived just before the 2020 lockdown did to put live theatre, and much of life, on hold. Spending time with Steven Levenson’s book for Dear Evan Hansen and the lyrics of Benj Pasek and Justin Paul offered the opportunity to look at how the show works as a piece of dramatic literature on the page.

Two things stand out. Firstly, it is a compelling, page turner of a read. The power of the lie drives the narrative forward relentlessly as Evan tries with increasing desperation to respond to consequences of what he has set in motion. It has the momentum of a thriller with enough depth of characterisation to support an emotional engagement with everyone on the stage. It draws us into this world as we wait for an inevitable, court-room style denouement to see what the consequences for Evan will be.

But this is where the second great strength of the piece lies. Having established with a ruthless efficiency the path Evan is on, there is a great subtlety in the way it subverts expectations and challenges its audience to think again about their response to what they have been watching (and reading) in the final scenes of the play. This is a challenge that I feel is often mistaken for flawed writing, and is in fact one of the musical’s greatest strengths.

***

In a review of Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, critic Michael Billington wrote “[w]hich is better? The consoling lie or the unpalatable truth? It is the enduring theme of American drama from O’Neill onwards”.

It is also a theme rigorously interrogated by that great influence on twentieth century American drama, Henrik Ibsen. The Norwegian playwright’s prose dramas probe the facades behind everyday life and the necessary “Iivsløgnen” or life-lies people cling to for meaning or sanity. The character of Dr. Relling in 1884’s The Wild Duck articulates this in a heated exchange with the idealist Gregers Werle:

RELLING: Take the life-lie away from your average man, and you take his happiness with it.

From Ibsen through to O’ Neill, Glaspell, Williams, Miller, Albee, the great tragedies of twentieth century American drama put the damage and the darkness of the everyday life-lie on the stage for audiences to adjudicate on the nature and necessity of truth. And it is very much worth considering Dear Evan Hansen in the context of this “enduring theme of American drama”. In an 2013 interview Levenson states:

I find Arthur Miller really fascinating, and I feel like he’s really dismissed lately as a playwright. We’re in this sort of Chekhov moment. When I think of Chekhov versus Ibsen, I put Arthur Miller in the Ibsen camp, the way they both foreground social commentary, versus basically being about these ephemeral life-moments. (Walat)

The fingerprints of Ibsen, Miller et al are visible as we see this classic theme re-interpreted through a twenty-first century lens in “a blank, empty space, filled with screens”. It is a musical suffused with characters crafting identities for themselves in a vain or/and valiant attempt to hold their sense of self together with a consoling lie. From the very beginning, Evan’s first letter to himself swiftly moves from the authentic self to the fabricated self:

EVAN: Dear Evan Hansen:

Today is going to be an amazing day, and here’s why. Because today, all you have to do is just be yourself.

(Beat)

But also confident. That’s important. And interesting. Easy to talk to. Approachable.

In the self-made, self-help pep talk language of modern America there are echoes of a desperate salesman trying to craft ill-fated identities for himself and his children:

WILLY. Walk in with a big laugh. Don’t look worried. Start off with a couple of your good stories to lighten things up. It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it — because personality always wins the day. (Miller)

Following an “utter failure” of an interaction with her son, the opening song of the show “Anybody Have a Map” introduces Heidi Hansen “just pretending to know” how to manage life, parenting and everything in between, both her and Cynthia Murphy just “making this up as [they] go”. At school Alana arrives with her “clearly rehearsed” list of successful summer achievements, Jared with “the kind of practised swagger only the deeply insecure can pull off”.

The opening scenes deftly establish the various personas the characters perform in order to endure the day. With Evan we see a character in search of a role. In Waving Through a Window he flounders with his anxiety and aloneness in a repeating series of questions that the musical provides two answers for, one he sees and one he doesn’t:

EVAN.

Can anybody see?

Is anybody waving back at me?(Lights shift and ZOE enters)

As if the answer to his question was standing right in front of him. The stranger who all his “hopes are pinned on” who “I don’t even know and doesn’t know me” does, in fact know him:

ZOE…

“Evan, right?”

Two words that suggest a moment where Evan could take a path of truth, but blinded by anxiety is incapable of acting authentically:

ZOE. Well / talk to you later.

EVAN. / You don’t want to sign my…?

ZOE. What?

EVAN. (instantly regretting his decision). What? What did you say?

ZOE. I didn’t say anything. You said something.

EVAN. No. Me? No way. José.

ZOE. Um. Okay… José.

(ZOE exits.)

Perhaps Connor is living life without a consoling lie, a path that leads us to T.S. Eliot’s famous dictum “humankind cannot bear very much reality”. In a touching moment of truthfulness Connor says to Evan “now we can both pretend that we have friends”, acknowledging their shared aloneness and the pretence of those around them, after cruelly signing his name “in an outsized scrawl, covering an entire side of the cast.”

But Connor does construct a lie, one that fuels his destructive impulse. Picking up Evan’s second letter to himself, an honest account of his unhappiness and loneliness, Connor turns this into his own narrative:

CONNOR. You wrote this because you knew that I would find it.

EVAN: What?

CONNOR. You saw that I was the only other person in the computer lab, so you wrote this and you printed it out, so that I would find it.

EVAN. Why / would I do that?

CONNOR. / So I would read some creepy shit you wrote about my sister, and freak out, right? And then you can tell everyone that I’m crazy, right?

Instead of consolation Connor’s paranoia builds its own lie that everyone around him thinks him a freak, thereby justifying his own feelings of self hatred. Is this truly who he is or just an expression of his unhappiness? In an earlier, controversial line Jared jokes:

Loving the new hair length. Very school-shooter chic.

The line is “ugly and offensive and juvenile… exactly what you would expect to hear from an actual teenage boy” (Levenson et al.) and it plants the idea that the look is “new”, blurring the boundaries between being the high school freak and playing the high school freak. A role Connor ultimately plays too well.

With Connor’s oversized name now emblazoned comically across his arm, Evan is backed into a corner as the life-lie becomes an inescapable reality demanded by the Murphys. In the principal’s office the grieving parents meet the only friend of their dead son, looking to make sense of their loss. Evan tries the truth: “Connor didn’t write this” but socially anxious people pleasers often make very bad decisions trying to keep everyone happy. Particularly if they are averse to conflict:

EVAN. They were so sad. His parents? His mom was just… I’ve never seen anyone so sad before.

The Murphys refuse the truth as we see both the appeal and the danger of the consoling lie. “They didn’t want me to stop”. Later, his response to Zoe looking for meaning from the letter is the same:

ZOE (difficult to ask) Why did he say that?… ‘And all my hope is pinned on Zoe’… Why would he write that?

(ZOE looks away, realizing that he doesn’t have the answer.

Seeing her disappointment, EVAN feels compelled to offer something)

If Dear Evan Hansen were to be structured as a tragedy this would be his fatal flaw, tested mercilessly by fate:

CYNTHIA. Larry. Look

(She points to Evan’s arm.)

His cast.

(EVAN looks down.

He lifts up his cast and realizes what CYNTHIA has seen: Connor in a sharpie scrawl.

CYNTHIA turns to LARRY, her eyes welling with tears of astonishment.)

His best and most dearest friend.

With the inevitably of tragedy the questions posed in Waving Through a Window are answered with For Forever. Thinking there is no one to wave back at him, and looked at expectantly with the desperation of grief, he creates someone who will. Invited to dinner with the Murphys, they struggle to maintain the happy family facade, recriminations and sadness spilling out, until Evan acts.

Cynthia’s distress grows more and more difficult for Evan to watch… Before even thinking, Evan finds the words tumbling out.

Those words create a fascinatingly layered piece of musical theatre. Taken completely out of context the song sounds like a young man expressing his love for his friend2. Placed in context, we know this friend is dead. We’re hearing this young man telling the grieving family about his friendship with their dead son. We also know that he’s making this up. The two were never friends.

And that could have been enough. An opportunity for satire or black comedy. But there’s two further places the writers go to, places lesser works would step back from which are central to the authors’ vision for the piece. It is worth quoting Levenson at length:

What was it that compelled people to want to publicly attach themselves to catastrophes? Why the urge to turn horrific events, events to which people might have no ostensible connection, into first person narratives?… we began to hone in on two possible answers. The first, most obvious one was that people are simply narcissistic and self obsessed and willing to exploit tragedy in order to gain attention or sympathy or both. It was easy to imagine what a musical based on that answer might look like; a scathing satire about our shallow, soulless times. It was, in fact, so easy to imagine this musical that we wondered what the point would be in writing it… what if, we wondered, people long to attach themselves to tragedy out of something far more fundamental, some deeply human impulse to connect… that they belong to something bigger than themselves. (Levenson et al. xiv-xv)

In a musical about a lie we have a bold and deeply truthful expression of the yearning for connection and to be cared for. As we discover later, Evan is rewriting his own suicide attempt. He didn’t fall from the tree, he let go. He is creating a friend who was there to care for him. And ultimately that friend is himself. An act of creation that expresses his need to love, rather than hate, himself .3

EVAN.

I’m on the ground

My arm goes numb

I look around

And I see him come to get me

He’s come to get me.

And ev’rything’s ok

Similarly, You Will Be Found, the show’s signature tune, has tremendous power when placed in context. Out of context and taken at face value it sounds like a somewhat superficial ode to hope and positivity. In context it’s overwhelmingly moving. Evan stands alone on the stage to announce to the school the creation of The Connor Project, a campaign to memorialise Connor and help people who are struggling. He loses his place in his speech, panics and is about to run. But he stops. His story “becomes, now, suddenly, a genuine discovery”. The musical representation of Evan’s speech is somehow both a collection of lies and deeply truthful. Because it is a wish. A willing into reality of a lie that is both healing and loving. The creators referred to this scene as “the church”, an apposite description as the characters gather to believe the impossible because it’s what they need to carry on, strive, to do better. It is moving precisely because it is a fiction.4

Whilst the lie begins to spread a sense of hope and meaning, the inverse is also presented. Earlier, in one of the musical’s most powerful moments, Requiem, Zoe rails against the narratives of grief and retrospective hagiography going on around her:

ZOE.

Why

Should I play the grieving girl and lie?

Saying that I miss you and that my

World has gone dark without your light

I will sing no requiem tonight.

The antithesis of Evan’s actions, Zoe consistently challenges the false narratives going on around her; the facade of the happy middle class family, Evan’s concocted initial version of Connor, Cynthia and Larry’s delusions about their handling of Connor. Even after she too is consoled by the lie (“You’ve given me my brother back”) she wants to move on and live in an authentic present:

ZOE.

So what if it’s us?

What if it’s us and only us?

And what came before

Won’t count anymore, or matter

Can we try that?

As her relationship with Evan grows she pushes against the evasions required by his lie, engineering what should be a normal meeting between the Murphys and the Hansens, but one where truth begins to leach out from his story. The lie serves many purposes for the characters in the play, but one thing it cannot support is love.

***

So a life-lie is born, grows and is seized on by a society quietly desperate to console itself in its loneliness and grief. Then self interest takes over and the play shifts gears. Evan has engineered the situation to please those around him. By Act 2 he begins to please himself. The wholly sympathetic protagonist is the easy path. What is a dramatic challenge and interesting and indeed human is the person trying to do the right thing then beginning to enjoy the bad. Returning to Ibsen, it is reminiscent of An Enemy of the People. Dr. Stockman, in the right, speaks up and condemns the poisoning of his town’s water. The easy path is to continue with our righteous hero. Averse to simplicity as ever, Ibsen challenges his audience. What if the hero we have aligned ourselves with begins to show questionable political views? A flawed human being trying to do the right thing, in the process revealing their flaws to the world. For those paying attention, Evan, vulnerable and in need of help, tries to tell the truth,fails, and lies to ease the suffering of the Murphys. Then his ego is boosted,his actions move from sympathy to selfish. And it makes us uncomfortable. Evan and his actions are problematical as all interesting characters should be. Because we are seeing people on stage depicted with honesty. Director of the Broadway and West End productions, Michael Greif described this purposeful sense of unease:

While you were rooting for Evan, you also were worried about Evan and condemning Evan and feeling a little complicated about what Evan was doing, And that duality was really thrilling to me. I thought this was pretty original. The audience gets to completely go with this kid’s yearning and fantasies – which is what musicals I think always have to do – but you also have a voice in the back of your mind, saying, “Wait a minute, there’s something so inherently off about this.” I thought that duality was thrilling. There’s probably less irony in Rent than in other shows I’ve done. There’s a tremendous amount of irony in Dear Evan Hansen. (Gerard)

As ego takes over the lie cannot hold, it falls apart along with Evan himself. Evan neglects the Connor Project, enamoured with his new life with the Murphys. Alana publishes “Connor’s” suicide note online to boost donations for the Project and its goal of buying and reviving the Autumn Smile Apple Orchard. The Murphys face approbation, online and off, until Evan can “bear it no longer”:

CYNTHIA. Look at what he wrote…

EVAN. He didn’t write it.

(Long pause)

I wrote it.

(Silence)

Evan is finally forced to finish the sentence from his first meeting with the Murphys. “Connor didn’t write this”, is completed with the vital final three words. “I wrote it”. He has to admit his trauma, not recreate it in a different form. We have been watching the story of someone not yet ready to be honest about their struggles, lying to keep it secret until the need for truth is overwhelming. Words Fail is the result, an excoriating moment of soul baring honesty:

No, I’d rather

Pretend I’m something better than these broken parts

Pretend I’m something other than this mess that I am

‘Cause then I don’t have to look at it

No one gets to look at it…

I never let them see the worst of me.

Cause what if ev’ryone saw?

What if ev’ryone knew?

Would they like what they saw?

Or would they hate it too?

The truth is out. Evan has confessed. The Murphys walk away. The one thing he has tried to hide throughout the story is exposed. Where do we go from here? As readers and audience members we wait expectantly for the consequences. What will be his punishment? Do the Murphys head straight to the police, or worse, take to social media to reveal the truth?

We expect judgement. And then, the play gives us something else. Evan returns home where his mother recognises the now viral note:

HEIDI. Did you… you wrote this? This note?

(Beat.

EVAN nods.)

I didn’t know.

EVAN. No one did.

HEIDI. No, that’s not what I… I didn’t know that you were… hurting. Like that. That you felt so… I didn’t know. How did I not know?

“No, that’s not what I…” This subtle but sudden shift of perspective jolts the audience out of the momentum of the lie narrative. Heidi reminds everyone that Evan is a young person who has has attempted suicide. While everyone onstage and in the audience has been swept along with his increasingly desperate attempts to hold his story together, either in sympathy or condemnation, with tremendous economy Levenson performs a narrative sleight of hand, stepping away from the compelling narrative to remind everyone watching that we already have one dead teenager in this story and we don’t need another. That we should pay attention to someone struggling, however unpleasant their actions may be. That there were two lies in the play. The one that we have focused on, that Evan and Connor were friends, and the other, more important, more dangerous, lie. The one Evan tells himself and everyone around him that he fell rather than he let go.

Online discourse that Connor is erased and that the play fails to engage meaningfully with the theme of suicide misses the point that we’ve been watching that theme rigorously explored for the past two hours. Were we paying attention or did we not see, just like the other characters, “that [he was] hurting like that”.

Dear Evan Hansen is also criticised for the apparent lack of consequence for Evan, but the musical is saying there is something more important than punishment at play here. Instead of the courtroom style denouement, a person in crisis is met with love and maturity. What Dear Evan Hansen dares to do is not destroy its tragic protagonist but instead treat him with compassion and acceptance. We have seen everything from Evan’s teenage perspective. The play gives us here at the end a mother’s perspective on her son. Instead of catastrophe we have So Big / So Small:

HEIDI.

Your mom isn’t goin’ anywhere

Your mom is stayin’ right here

No matter what

I’ll be here…

When it all feels so big

‘Til it all feels so small.

(EVAN goes.

His mother lets him go.)

You’ll see. I promise.

Do we want to see a public humiliation and another suicide? Demands such as these also deprive Cynthia and Larry of a significant moment of grace. In a choice between retribution and compassion they choose compassion. Why would they choose to hurt another difficult, harmful young person? Once again, the writing in the epilogue is beautiful in its economy:

EVAN. They never told anyone. About Connor’s, about the note. About… who really wrote it.

(ZOE nods.)

They didn’t have to do that.

As an audience member we may not like it, but it’s not our decision to make, it is the Murphys and it is a decision consistent with their character.5 Just as Zoe’s choice is her own. Standing in the replanted orchard, it’s left to the most truthful character in the play to decide, with acceptance, compassion and understanding, the ultimate value of a lie:

EVAN. …why did you want to meet here?

(A long pause.

ZOE looks around.)

ZOE. I wanted to be sure you saw this.

***

In a choice between the consoling lie or the unpalatable truth Dear Evan Hansen suggests that both have their role to play in navigating an increasingly polarised and binary online world. Early in the play, in a “Chekov’s gun” moment, Jared foreshadows Evan’s Act One apotheosis:

… like last year in English when you were supposed to give that speech about Daisy Buchanan, but instead you just stood there staring at your notecards and saying ‘um, um, um’ over and over again like you were having a brain aneurysm.

A small thread linking one fantasist of American literature driven to recreate himself with another. A different iteration on a timeless theme encapsulated in the hopes of James Gatz on his way to becoming Jay Gatsby:

It eluded us then, but that’s no matter- tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther … And one fine morning- (Fitzgerald)

Instead of “boats against the current borne back ceaselessly into the past” we look ahead. Evan composes a third draft of a letter to himself:

EVAN. Dear Evan Hansen. Today is going to be a good day and here’s why. Because today, no matter what else, today at least… you’re you. No hiding. No lying. Just… you. And that’s… that’s enough… Maybe someday, some other kid is going to be standing here, staring out at the trees, feeling so… alone… maybe this time, he won’t let go. He’ll just… hold on and he’ll keep going.

He’ll keep going until he sees the sun.6

You can be destroyed by the imagined, the unattainable or elevated by it, by what you build in the attempt to reach something beyond attainment. Dear Evan Hansen is a new telling of the journey towards that fine morning, that good day, when we can see the sun.

Works Cited

Billington, Michael. “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof | Theatre.” The Guardian, 18 September 2001, https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2001/sep/19/theatre.artsfeatures2. Accessed 19 May 2024.

Eliot, Thomas Stearns. Four Quartets. Faber & Faber, 1996.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby (Penguin Modern Classics). Penguin UK, 2000.

Gerard, Jeremy. “Tony Watch: ‘Dear Evan Hansen’s Michael Greif On ‘Sensational’ Ben Platt And The Inner Lives Of Children.” Deadline, 2017, https://deadline.com/2017/05/tony-watch-dear-evan-hansen-michael-greif-on-ben-platt-1202095611/. Accessed 19 May 2024.

Ibsen, Henrik. A Doll’s House and Other Plays. Edited by Tore Rem, translated by Deborah Dawkin and Erik Skuggevik, Penguin Publishing Group, 2016.

Ibsen, Henrik. Hedda Gabler and Other Plays. Edited by Tore Rem, translated by Deborah Dawkin and Erik Skuggevik, Penguin Publishing Group, 2020.

Levenson, Steven, et al. Dear Evan Hansen: The Complete Book and Lyrics (West End Edition). Nick Hern Books, 2019.

Levenson, Steven, et al. Dear Evan Hansen: Through the Window. Edited by Stacey Mindich, Grand Central Publishing, 2017.

Miller, Arthur. Death of a Salesman: Certain Private Conversations in Two Acts and a Requiem. Penguin Books, 2000.

Walat, Kathryn. “The Unavoidable Momentum of Steven Levenson.” The Brooklyn Rail, 2013, https://brooklynrail.org/2013/06/theater/the-unavoidable-momentum-of-steven-levenson. Accessed 19 May 2024.

- All credit to Matthew Cohen Marketing Creative for the wonderfully distinctive blue polo shirt, thumbs up poster. Behind the “everything’s ok” signifier is something broken and painful, forced into a position of enacting wellness. A brilliant bit of paratextual imagery. ↩︎

- Another way in which many people have expected one thing from the musical and interpret not getting it as poor writing. Just because Dear Evan Hansen isn’t a gay coming of age story doesn’t mean it is therefore a bad piece of writing.

↩︎ - Something that makes this performance of the song particularly impactful. ↩︎

- And musically, that well used I–V–vi–IV chord structure is also exactly what is needed, comforting and familiar like an embrace reaching out from the stage across the audience. ↩︎

- Including the public exposure of Evan is one of the many ways the film fails, rushing through an aftermath that cries out for story. ↩︎

- Is there an echo, an inversion, of Oswald’s bleak, final lines in Ibsen’s Ghosts “mother, give me the sun” in Evan’s evocation to step into the sun and see sky for forever? Both plays have emblems of hope built on lies, but the orphanage of Ghosts burns while the orchard of Dear Evan Hansen grows. ↩︎

Leave a comment